|

God Has Sent To Us One Of His Angels -- |

"Sissel" is the Norwegian derivative of the English name "Cecilia" It is a rare and unusual name, commonly found in Denmark and Norway, where it is cherished for its traditional roots. The name is sometimes associated with notable figures in music and arts. Its connection to nature and strength makes it suitable for individuals that embody these qualities. Objectively, it is most commonly associated with the Latin word "caecus", meaning "blind or dim-sighted". Subjectively, however, the name is also linked to Saint Cecilia, a Roman martyr, considered to be the patron saint of music and musicians. This connection often leads to interpretations of Cecilia as representing spiritual vision, hidden beauty, or a girl with vision more than sight. It symbolizes the depth of perception beyond seeing (on the surface). The above listed three DVD collections EACH contain OVER five hours of "Angelic and Heavenly Sights and Sounds", designed to transport the listener from this world of earthly cares into Sissel's World of Ethereal Beauty. |

|

|

To Listen to over 500 of Sissel's Captivating Performances - Broken Down Into 18 Categories & Arranged in Chronological Order -- Please Click HERE. |

I am presenting this because I think that it offers an EXCELLENT insight into one of the major factors (I believe) that contributed to Sissel's VERY humble, modest, and unassuming personage. I believe (as do MANY of her fans) that THIS quality is one of her MAJOR characteristics that makes her so unique and GREATLY loved !! How many individuals in today's "entertainment industry" (ESPECIALLY in the USA) do you know who possess her IMMENSE and overwhelming beauty, charisma, fame, talent and versatility - who are anywhere near as authentic, humble, modest, unassuming and "real human beings" as is Sissel ?? I won't elaborate on WHAT this factor is - the following chapter does that job quite well. There is a paragrph (highlighted in yellow) near the end of the chapter that mentions Sissel by name. Click [ HERE ]. Another interesting fact came to mind as I was writing this. It seems illuminating (to me, at least) that when it came time for the birth of God's Son, Jesus - it was in an obscure little town, in a humble stable, with only the animals and shepards in attendance. When God wanted to create HIS "Superstar" - He brought forth His Sissel in a small country, in a small rurally situated city, born to very average parents, in a very average home. Had she been born in the USA, she would have been "devoured and (metaphorically) killed" (just as the King in Israel sought to kill the baby Jesus) by the tyrannical "American Music Production Machine". As a matter of fact, Sissel states that when she was about 18, she was in the USA and was offered an opportunity by one big music producer to be made into what he considered a "Great Star". Fortunately, God gave Sissel the presence of mind to refuse. Had she not, we would never have been privileged to know the phenomenal being that she has become today. She would have been just one more "cookie cutter clone", manufactured for the benefit of the Music Industry, and tossed aside for another version of the same when her usefulness to it had expired !! It is even MORE interesting that a few years later, Sissel felt that she was NOW ready for an appearance in the USA. However, despite her efforts and a number of tours and appearances in the USA, she never really "broke through" into the "pop music arena" nor attained very much exposure nor popularity there. Read an interesting article on "Janteloven" HERE. ****** To view a short video (7 minutes) revealing how this enviroment played out in Sissel's life, contributing toward the making of who and what she is today [ CLICK HERE ]. Please Click [ HERE ] to read a short article on my perspective regarding Sissel's Read a companion article [ HERE ]

JEG ER NORSK

"We" could mean all four-point-something-million Norwegians- at least it seems the whole country is here today -- but here, "we" is our family plus Aaron, my visiting brother, and our friends the Karissons and the Bakkens. We're their guests at what is, right along with Christmas or the Holmenkollen Ski lumping Championships, the peak event of the year. It's Norway's Constitution Day, when the country celebrates its final cut from a tangled history of imposed rule by Sweden. The long path toward the victory of self-determination began when Norway drafted its first Constitution in 1814 and claimed autonomy, then skipped back under Swedish rule, until finally declaring itself independent on May 17, 1905. I've got an idea of what national holidays like this are about, at least those I've witnessed close up in Austria, Germany, and the States. So when Bente Karlsson tips me off early in the week that this is very hoytidelig, meaning we should all dress in our ?nest attire (the Karlssons and Bakkens will be in national costume), I'm baffled. Hoytidelig, before I look it up, means, literally, "high time-ly." But a "high time" to the American in me means firecrackers, high school bands and marching squads, stilt walkers, clowns scooping manure, and bloated cartoon characters blimping in the air above Main Street, noise makers, megaphones, boats with beauty queens who dispense taffy. A bazooka- and-hullabaloo sort of "high time." How we're all going to sit in plastic lawn chairs in the gutters and manage our Coleman ice chest lunch on a blanket while dressed in our Sunday best has got me curious. Randall's going to look silly waving sparklers in a tie. I'll have a hard time diving for taffy in heels. Bente and her Swedish sister-in-law, Pia, have to gently school me here about what a high time means in Norway. Bente was lucky; she knew the codes from birth. Pia, married to Bente's brother, Borre, was less lucky because she was a latecomer. She was adopted into Norwegianness at around twenty, but made up for her lateness by being a quick study. Now, twenty years later, she is totally indistinguishable (in accent and loyalties) from her whole Norwegian family. Bente's husband, Ian Ake, is also a Swede, meaning he and Pia could have formed a little resistance had they been rabble-rousers. But they didn't. Even when not around the rest of the family they spoke Norwegian to one another. Something about Norway worked like a spell. "No, Melissa, we won't need Coleman ice chests," says Bente.

What? No stretch convertible limo dressed as a paper mache alligator? (I know, I know. I couldn't picture a parade without one any more than you can.) "What there will be," Bente tells me, "is barna." "The children wave to King Harald and Queen Sonja," Pia says softly.

I start to get the point, take my friends at their word, and dressed myself, my husband, and two children accordingly. Shoes and handbag matched. Ties cinched. Hair licked in place. We are set for a high time. Down in Oslo's city center, the procession begins, and if we crane our necks just enough, all of us in our party can see the beginnings of the barnatog, or children's parade which, like a colorful tide, is pushing its way from the bottom of Karl Iohans street up past us and toward the palace where the royal family waits to wave. Considering the throngs, we're pretty well positioned. All of us, that is, but our own children, who seem to be missing whatever magical Norwegian gene keeps a best- dressed preschooler solemn while standing for two and a half hours in a frigid public square waiting to catch a glimpse of even one of several hundred flag-waving, well-wishing, elementary-school-aged children. Thirty minutes into this, and already it's becoming clear that whatever it takes to really appreciate the moment, Parker doesn't have it, so Randall practically has to sit on our boy to keep him from hucking dusty gravel at every national costume in sight. The name for the sumptuous hand-embroidered heavy wool (and very expensive) national costumes is bunad, and on this 17th of May there are many, many bunads to huck gravel at. Aaron -- you would love my baby brother -- is twenty-something, single, camera-wielding, and has long since disappeared into the blonde bunad forest. We won't see him again until later after he's taken two-hundred pictures and four pages of names and phone numbers. Then we hear music -- singing -- nothing piercing or piped-in or thundering from truck-top loudspeakers; just the mellow stream of children's voices sailing atop the sea of small bodies and banners that is slowly coming our way. The sound is artless, unaccompanied, uncomplicated and pristine. It hushes the talking among us, freezes Parker mid-huck. It's some sort of Happy Camper song, and Tobias and Ioachim Karlsson, handsome teenagers in traditional costume, seem to know it like most everyone surrounding me. They're half-grinning, nodding, and humming. Pia and Borre are lipping the text with their girls, Ninnie and Rikke, recalling what is, I'm wagering, a barnepark standard. The first wave of singing children gushes past me, their eyes alternately furtive, worn-out, enthusiastic or mischievous, and the women in my group let out a collective coo. So much tousled white hair, so many missing teeth, such innocence and simplicity merged into one bright stroke of color. Something happens to my impatience. I stop toeing gravel and myself softened and stirred at once; one great big shivering smoothie. The Karlssons' oldest son, Christian, is standing next to me. Towering, actually. He's a well-limbed tree, a sparkling sample, if there ever was one, of Norwegian young manhood, Aaron's age but he seems at least a foottaller (and Aaron's tall himself). Christian can remember the time he got to ga! pd tog (walk in the parade) and hilse pd Kongen (greet the king), and gets that faraway, kind of homesick look in his eyes. All these people around me, I'm realizing, had done it, in fact; herded up Karl Iohans street with their school class, bearing flags, singing school songs from some common Norwegian Folk Melodies binder. Everyone has to do it once, I'm told. It's a rite of passage. Beginning toward the bottom of the river of children rises a modest rustling of applause, the sound of a sudden surge of water coursing over rocks. "Rus," Christian says to me, not taking his eyes off the scene as if he's a storm watcher and is whispering a tornado warning. I get up on my tippy-toes so I can see two big patches of red and blue like vibrating, opposing soccer teams, coming at us. Rus is an untranslatable term really, but is roughly the Norwegian equivalent of "high school senior." These graduating classes spend the whole last month of high school dressed in either a red or blue jumpsuit, the color signaling their projected direction of further study: liberal arts (red) or technical/trade school (blue). Like competing squadrons of mechanics, they then drive around in big buses they've bought collectively, painted, and plastered with graffiti. Starting in May you see these buses littered all over the landscape like escapees from a KOA campground. The kids form kibbutzim around these parked carcasses: it's where they live, get drunk, get stoned, get wild, get crazy. The Partridge Family meets Woodstock. At first glance, the Rus tog is an absolute head-banging opposite of everything dainty the children were: they're rowdy and obnoxious; they're barking Metallica lyrics and shoving each other into bushes, and some kids who come closest to us smell of booze though it's not even noon yet. Then there are those goofy jumpsuits. I can't get my brain around them, and my mind wanders off into all sorts of dim deviations about jumpsuit origins, jumpsuit design, jumpsuit factories, and shipping orders, and overstock. Then suddenly a girl with brown braids and blue polka dots painted all over her red jumpsuit and face is launched from someone's shoulders and lands, arms flailing, around Randall's neck. A real, speckled bombshell. We exchange glances, my destabilized husband and I, and, laughing hard, help her stagger back into the red and blue current, the blue polka dots growing purple on her flushed cheeks. Borre steps in to explain away his country's bad manners: this is all within the understood limits of Rus decorum, he says. The kids know how far they can go, Christian says. They're under so much pressure to conform all year long, Pia says, that now they know they can let loose. There are limits, Ian Ake nods. Always limits, Bente double nods. These big kids aren't so different from the little ones, I think. Each tog offers a context, which empowers its participants to do things they probably never would do were they alone. Children, surrounded by like children, buried in the security of a group, can yodel in front of thousands while marching right up a main thoroughfare to greet a king and queen. Rus, surrounded by like Rus, buried in the uniformity of a group (and beneath the anonymity provided by ill-fitting Jiffy Lube duds) can catapult themselves into crowds and carouse 'til the cows come home. All without consequence. They can do it, in fact, with the whole country's -- not to mention the king's and queen's --blessing. Maybe I need to give you a closer translation for the word tog. A tog is both a "train" and a "parade," the dictionary will tell you. "Train" gets you close: it's a moving, linked vehicle that progresses on parallel tracks. Although composed of pieces, it forms a unit and that whole unit travels in absolute unison. A Norwegian tog is not really a "parade" in the American sense but is, I decide, a "procession." A processions about community over the individual: the engine, cars, caboose, and tracks make a train. We move together. We sing together. We wear train conductor outfits together. Individual children are no longer Mette, Sven, Kari, Astrid, or Geir. They're something else, a fused something else, and one of their songs exclaims it: " Vi er norske barn!" ("We are Norwegian children") The teens, too, are no longer Tarjei, Silje, Louisa or Anne-Marit. They're a bigger thing, a big amalgamated identity, as one of their chants ex- claims: " Vi er norske Rus!" At no point do I hear, "We Are the Champions." Why? Because a procession makes you think horizontally, sideways, always keeping things level and watching out for your neighbor, we do not compete or race -- we will all arrive at the royal palace as one. There are no honking jalopies and unicycle flame throwers, no entertainment in that sense to distract us from the essential. The mood here is subdued, the sound level is restrained, Rus included. A procession is horizontal -- solemn -- and a procession is Norwegian -- and Norwegians love a procession. Unlike a procession, in a parade the individual I comes before the communal We. You advertise disparate and distinct entities. In an American parade you parade things; you advertise. Period. Your normal Fourth of July parade is a three-hour string of competing floats, competing bands, competing beauty queens, competing convertibles, all bearing banners for the likes of State Farm Insurance, the Shriner's Charity Car Wash, or Porky's All-You-Can-Eat-Rib-and-Spud-Split-Your-Gut Buffet. It's a distinct entity upon distinct entity panorama tied together by an emcee and a few renegade jugglers. A parade advertises not only its individual parts, but its cause (on the Fourth of July its ostensible cause is Liberty), and that with clamoring, sometimes earsplitting, commotion. Think of Katie Couric's prolonged hoarseness after shouting into her mic over the din of the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. But our pilgrim fathers were solemn guys, I thought. So what? So an American parade is loud. We Americans would like to think it's loud because it's proud. It's vociferous, boisterous, explosive, like fireworks. It's supposed to get you up and outta your lawn chair. It's designed to make you think vertically, head-and-shoulders-above-the- rest. Up! Sky's-the-Limit! Its flow is punctuated by the sharp blasts of trumpets, their bells pointed to the clouds. Its beat is aggressive, combative even, with snare drums rattling your nerves and big bass drums heading up the rear, quaking the ground and shaking your Coleman ice chest. It's a spectacle, entertainment, sometimes breathtakingly tacky, sometimes -- think of a Sousa march detonated by a polished marching band -- spine-chillingly stirring. A high time -- a parade is American -- and Americans love a parade. Our speckled Rus friend has just regained her footing when a voice over a loudspeaker announces flatly that we will all now sing our national Hymne. Rus and barna and every single body across the stretch of my vision stops dead in their tracks. And I hear the song for the first time, soft orchestral score broadcast over the heads of thousands of common singers whose voices weave in and out of tree branches: ]a, vi elsker dette Zandet,

Yes, we love with fond devotion This, our land that looms Rugged, storm-scarred o'er the ocean, With her thousand homes. I understand at least that much of the text, and can't help but draw a comparison between it and "The Star-Spangled Banner," a very different poem entirely. The first is a hymn to the land itself -- the soil, the mountains, the pines, the water -- to the country's violent beauty, wounded physicality, to its protective powers and to the powers that have protected it. It looks horizontally, drawing together community. "The second is an anthem constructed around a military scene and the image of the flag held high. It looks vertically, over the ramparts where there are rockets and bombs bursting in air, and over the towering steep where it waves in triumph over the land of the free and the brave. Whatever the comparisons and contrasts are, the moment is a Kodak one. Christian's baritone is barely discernible, but I'm taking his lead. We sing two verses while everyone stays perfectly still. I can pick out individual children's, teenagers' and adults' voices, and I feel I'm standing not only in sudden harmony, but in a sacred moment. I turn when the song ends to see Christian, and he shakes his head once, takes a deep breath, and closes those eyes to whisper, "leg. . . er. . . Norsk." --------- I am Norwegian. What it means to be Norsk fills up more than a few dinner conversations over the five years we live in Norway. But on that first 17th of May we get a good overview in one evening eating outside on the Bakken's terrace. Between Borre's grilled ribs and salmon steaks, Pia's mustard herring, Bente's new potatoes, our first taste of lefsa, a special bread, all washed down with nonstop sparkling cider, we start to peel back the layers of Norway's very special breed of patriotism. To understand being Norwegian, Bente begins, you must first understand Janteloven. Ha, but I'd already learned about that word from Idar, a common friend of ours from church who happened to be a linguist. I told the whole 17th of May table this same story I'd told Idar. It happened at barnepark: Tante Britt approached me one afternoon when I arrived to pick up Parker and Claire at the Blakstad fence. Her eyes lowered, Britt told me there was a problem.

"Et problem? Hva er det?" What was the problem, I needed to know.

So it was to our linguist friend, Idar, that I had turned. He explained the whole context behind the raisin ban and anything else that might not be allowed because it might distinguish one person from another. Janteloven. Idar cocked his head, let out a big sigh, swinging his head languidly from left to right. And then he went on to tell me that Janteloven (literally; the Laws of Jante) is a creed governing a fictional village JIante) created by Danish/Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose in his novel, En flygtning krysder sit spor (A Refugee Crosses His Tracks). In this work, the author satirizes the Scandinavian effort to reinforce egalitarianism by squelching ambition and discouraging originality. The ten laws of Jante are as follows:

- Don't think that you are special.

In light of these laws and in retrospect, I now understand that I got away with being outspoken, driven, and maybe a bit quirky (red Dolly Parton boots) only because I was an outsider, an American. The rules of Jante didn't really apply to me. Or at least, they did not apply to me as seriously, say, as they did to my children, who were testing limits with their snack food. Pushing the raisin box. Janteloven: my Norwegian friends had mixed feelings about it. Kjersti, a young Norwegian student, had cautioned us early on about responding correctly to the typical greeting, "Hvordan gzir det?" (How are you?) Kjersti lowered her voice to emphasize that it was socially unacceptable to say anything but "just fine." Anything else would be excessive and would border on self-importance. It was not suitable, not Norwegian, to be anything more than just fine. Sure, you can answer that you're bad or awful, but not great or terrific. Because neither you nor your day, mind you, can be going any better than your neighbor's. Some friends loved to tell me how, when there was a temporary stretch of oil rationing, their King Olav rode the public streetcars just like everyone else did. Skis in hand, poles slung over his shoulder, His Royal Highness was the model of Janteloven equality. A local minister who invited me to solo at an event in his church took me down after the concert into the sakristie, or casket room. Every last casket he showed me -- dozens of them lined up in the room -- was a simple pine box. No elaborate sarcophagi, no mahogany coffins lined in red velvet, no hand-carved walnut objets d'art with ornate gold plated hinges and brass locks and wiring for an internal stereo system. Every last one was the selfsame pine box. Every Norwegian went into the earth in the identical box. King Olav, even, the streetcar king himself, would be buried just as the streetcar ticket checker himself, in one of those boxes one day. "And his headstone?" I asked. "Same size as everyone else's," said the minister. "The state has set strict guidelines regarding height limit, and there are equally strict rules for inscriptions, font, decoration." I got excited, if you can imagine the scene, looking at a row of nearly identical grave markers lined up like dominoes against the back wall. The minister might have thought I was irreverent, but then he'd probably never seen Napoleon's, Mao's, or Lenin's tombs. He merely smacked his lips, wrinkled his brow, and smiled the worn out smile of someone who's watched plenty of these boxes go underground. In death, as in life, in Norway there would be no tall-poppy or tall-headstone syndrome. A highly trained doctor of science at Randall's work was formally forbidden, after a vote taken among the secretaries, to use her "Dr." title when signing letters. "What happens with me, then," the ringleader secretary asked, "who doesn't have such a fine title?" Barge Ousland, polar explorer, who had trained for years by dragging stacks of winter radials tied to his waist in and out of fjords in various degrees of frozenness in order to complete the two-month-long, first-ever solo crossing of the Antarctic, and whom Randall was able to meet and interview on the topic of individual motivation -- even he called that stupendous feat a "good challenge" but nothing to "act proud about." Another friend, Rut, taught me there were addendums to the ten laws of Iante. We knew already that you should never brag or express confidence or be enthusiastic about yourself. But you should never brag about having a good job. Or a strong horse. You should not mention the brand of your car. Your tractor. The location of your house. If it has a deck, view to the water, plumbing. You should not publicly praise your husband. You must not strive. You are not "gifted." You are not entitled to any exceptions for any reason due to talent, birthright or ambition. Keep your head low. Keep your personal goals knee-high where all of us can reach them, just like you. Do not distinguish yourself. Think small. And especially, you shall never, ever, ever brag about your children. Call them whatever you want, but it must be average or worse. By about now, I'm almost certain there are some Norwegians reading who'll take umbrage with what I'm saying. Some will claim I'm exaggerating, or more likely, that I'm equating being laid back (as Norway generally is) with being suppressed in some fundamental way (which of course not all of Norway is) or that these people are somehow proud of their humility (which, actually, many Norwegians, laughing at the topic and themselves, say is sometimes true). But two things are true beyond question. First, you get five minutes into a chat with a Norwegian and, bingo!, Janteloven pops up. Everyone has their stories. And believe me, some are at least as interesting as mine. Second, times are rapidly changing in Norway, as everywhere. Last time I visited, there were small red boxes of raisins available in every grocery store. I went on to learn more about the practical application of Janteloven. It helped me understand why my neighbor's seven-year-old daughter had been forbidden by the principal to ride her bike to school even though it was a four-minute ride on a marked path directly from her back door. Was there really a safety issue in question? No. It was because not all of the school children are able to ride bikes at the age of seven. And if all can't bike, yet she does, they would feel underprivileged. The girl should not incite feelings of inferiority in others. Of course, the school policy allows for all children, beginning at age ten, to ride bikes to school. But don't be surprised, if you bike before that age, to find your bike chain confiscated by undercover vigilante Janteloven enforcers.

There was, as I'd noticed that first winter in Norway, one special twist to Janteloven. I witnessed this at the Olympic Games. Even before the broadcasting of the games began, Norway's own press had the entire country set up to not expect much from these games. The Norwegian officials, analysts and commentators prepared their country for a passable, but not extraordinary, kind of show. "The most ordinary Olympic Games ever!" the campaign seemed to go. We're a little country, the media soberly reminded everyone. Lillehammer is a little town. Will you look at us? We have little experience in big happenings. We're simple folk. Small fries. Pitiful, meek trolls, all. Who can help but compare the manner of the athletes like Italian downhill racer Alberto Tomba (also known as "Tomba la Bomba"), the swarthy and showy Casanova of the Slopes who takes the silver medal in slalom, with Norwegian gold medalist in the super-G, Kjetil Andre Aamodt? Muscle-flexing, skirt-chasing, media-hungry Tomba seems to have a whole, manicured speech in his back pocket, fingertip-kissing finale and all. There's no question in anyone's mind (including Tomba's) that this Adonis is God's gift to the slopes. Amid shrieking worthy of a rock star, he swaggers off of my TV screen. Then the camera pans to Aamodt. He's looking more like he just sauntered in from clearing an entire forest than from waxing his brows. He's comfortably disheveled, half-smiling, and clearly camera-shy. "So how does it feel, Ka-jettel, to be one of the most decorated Alpine skiers in history?! Tell us how that must feel!" The American reporter leans into the question.

Now, when Norwegian public voices come to wish athletes the best of luck (because they'll sure need it, the tone implies), the athletes them- selves bow their heads, already contrite, promising to, oh-ho-hum, give it their best shot. Never do I hear the slightest hint of confidence, even passionate determination. And while I wait for it, I never once hear a single participant admit to actually wanting -- imagine this -- to win.

That's what you get from telling your kids to mind their raisins and their Janteloven.

|

|

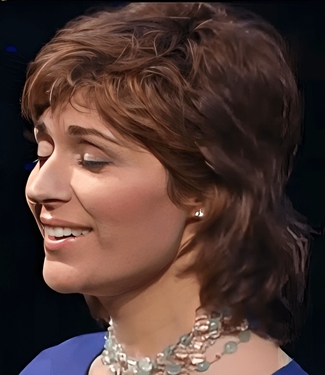

Sissel Kyrkjebø, the international singing sensation and national treasure of Norway, is established as one of the world's leading crossover sopranos. Her angelic and powerful voice has made her a national institution. She has contributed haunting vocals for the soundtrack to "Titanic" and "The Lord of the Rings", as well as selling over ten million solo albums. In 2006, her album, "The Spirit of the Season" with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir went to number one on the Billboard Classical Charts, and received a Grammy nomination. She captivated the whole nation of Norway in 1986, when she sang during the break at the Eurovision final in Bergen - only 16 years old and dressed in a white bunad (traditional Norwegian folk costume). Since then, her fame and success have just continued to soar. She has been praised and acclaimed at home and abroad, and masters both the small and the very large formats -- everything from American TV shows to film music. Her singing knows no bounds - she masters all genres - from opera to rap! She has sung all over the world, and has performed duets with singers like Charles Aznavour, Andrea Bocelli, Jose Carreras, Placido Domingo, Mario Frangoulis, Josh Groban, Brian May, Neil Sedaka, Bryn Terfel, Russell Watson and rapper Warren G. Her list of achievements makes you dizzy -- ranging from Schubert to Deep Purple - "O mio babbino caro" to "Udsigter fra Ulrikken". Truly a very remarkable talent and voice that only comes once in our lifetime! It is difficult to say anything that hasn't already been said about Sissel, but "National Treasure" and "Norway's Joint Voice" are two of the terms used about the "girl from Bergen". In 2005, she was knighted by the King of Norway, being the youngest ever to receive this honor. In 2022 she received the "Seven Pillars of Humanity Creativity Award" in recognition for her years of humanitarian work around the world and actions representing the good in humanity. On June 28, 2025, Sissel finally performed with the Kristiansand Symphony Orchestra - on the island of Stangholmen - during the Risør chamber music festival. This was her first appearance at this six day festival. In 2025 she was awarded the "Anders Jahre's Culture Prize". This prestigious Norwegian prize, often described as the country's largest honorary award for outstanding contributions to cultural life, was presented to her alongside two other musicians. The total prize amount was NOK 1.5 million, shared among the three recipients. She also received a hand-calligraphed diploma and a beautiful watercolor by Håkon Gullvåg. Sissel was also honored at the "KK Gala 2025" annual awards event celebrating inspiring Norwegian women across various fields for their achievements, contributions, and influence. She was awarded the honorary prize during the gala for her long-standing career and cultural impact. For Biography Sites, click: [ HERE ], [HERE], [ HERE ], [ HERE ], [ HERE ], [ HERE ], [ HERE ], [ HERE ]. |

| portraits of Sissel [ HERE ]. Note: It is a VERY large file, 900 Mb. |

| PLEASE NOTE: In the event that a large window containing an ad should appear in the middle of the download screen, simply click on the white "X" above the upper right corner of the ad to close the ad. ****** PLEASE - Be sure to read the "IMPORTANT NOTICE.txt" in the .ZIP file !! | |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

Firstly, we are pleased to offer this Commemorative "Collector's Edition" of the "Reflections Series" that Sissel released in 2019. It is a four disk DVD set consisting of 51 Music Videos and 51 corresponding "Talks" Videos. Please

Firstly, we are pleased to offer this Commemorative "Collector's Edition" of the "Reflections Series" that Sissel released in 2019. It is a four disk DVD set consisting of 51 Music Videos and 51 corresponding "Talks" Videos. Please  Secondly, we are VERY pleased to offer this four DVD Commemorative "Collector's Edition" -- "Platinum Treasures", consisting of: "Sissel w. the Tabernacle Choir", "Strålende Jul w. Sissel", and a collection of "Platinum Favorites". Please

Secondly, we are VERY pleased to offer this four DVD Commemorative "Collector's Edition" -- "Platinum Treasures", consisting of: "Sissel w. the Tabernacle Choir", "Strålende Jul w. Sissel", and a collection of "Platinum Favorites". Please  Thirdly, we are IMMENSELY pleased to offer this four DVD Commemorative "Collector's Edition" -- "Sissel's World", including original songs with lyrics written by Sissel herself. Please

Thirdly, we are IMMENSELY pleased to offer this four DVD Commemorative "Collector's Edition" -- "Sissel's World", including original songs with lyrics written by Sissel herself. Please

"Egalitarianism -- an Angel of Light ---- or of Darkness ??"

"Egalitarianism -- an Angel of Light ---- or of Darkness ??"